In the world of enterprise technology, it can be easy to become blasé about big figures. Nobody bats an eyelid at billion-dollar deals, even when they’re being made for companies that have never turned a profit. It can be a puzzling landscape, where only transactions of eight figures plus make people sit up and take notice.

But behind the numbers, there is still room for marginal gains to be made, which rolled-out across an organisation can quickly add up.

Around a year ago, Mihran Hovnanian, CIO of Baker Hughes’ Measurement & Control Solutions division, began to collate a list of what he calls ‘unreliabilities’ of assets, essentially measuring how many hours of downtime pieces of machinery register each year. The results were not particularly encouraging.

“We found some assets with 4,000 hours downtime per year,” he says, “and before you try to start working it out, there are 9,000 hours in a year.” Hovnanian recounts that in this scenario machines are fixed, and the recommendation is that the machines are digitalised to provide live information, so that teams can react more quickly to faults.

“But as a multi-national company, we have over 100 factories globally and thousands and thousands of machines – I can’t go around detailing all of them,” he says. “So, we started to think that there should be a method to digitalise in a self-service way. We need a level of simplicity where you don’t need a load of technical skills to do things. That’s where Nick came in and did something really beautiful.”

Nick Clark is GE Measurement & Control Solutions’ Global Commercial SAP Implementation Leader. He is also a long-time user and committee member of a local squash club close to GE’s facility in Leicester, UK.

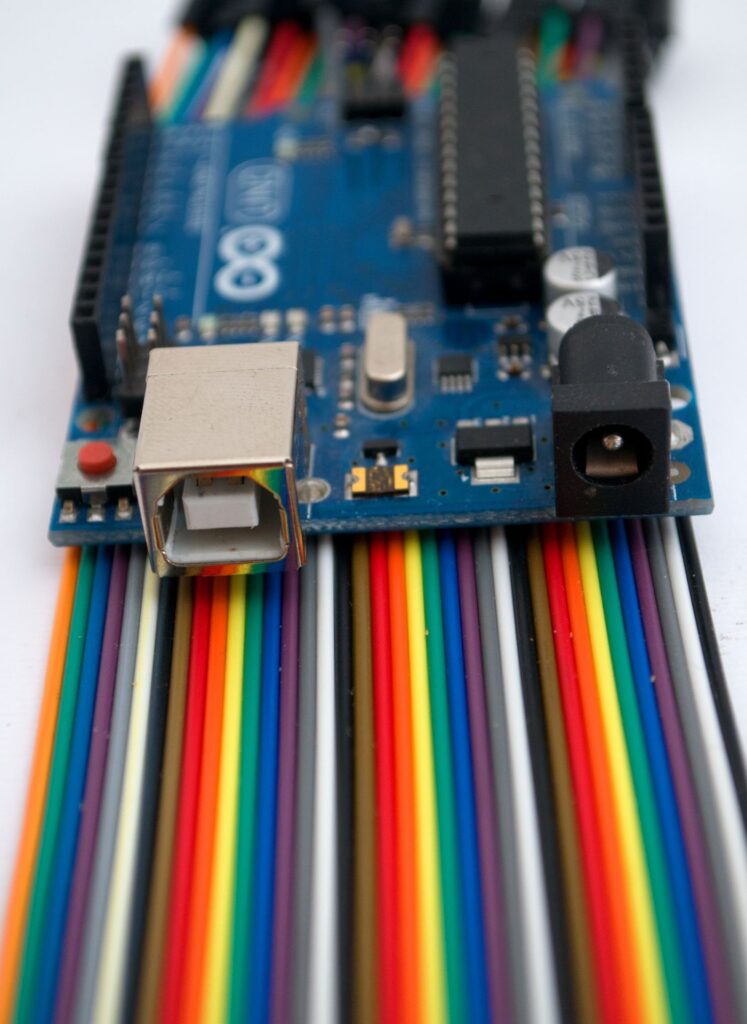

Clark saw it as a perfect testing ground for a small pilot project, using a Raspberry Pi, circuit board and $1 thermostat to monitor the club’s commercial hot water system supplying approximately 50 shower uses per day. The overall cost of the unit was less than $50.

The kit monitored four temperature sensors and one pressure sensor, and found cylinder temperatures fell considerably overnight, large pressure variations and that the boiler ran for five or six hours in the morning but never reached full output temperature. Information was transmitted over WiFi to a website every 10 minutes.

Using the data, Clark was able to make a number of fixes meaning good overall pressure control, only a slight decrease in cylinder temperature overnight and the boiler running for just half an hour in the morning to reach full output temperature.

Since the changes, the club has seen its annual bill for the system fall $960 a year – a saving of 32%.

“No digital team is going to get out of bed for $1,000 so this whole self-service digitalisation could really make a difference,” says Hovnanian. “Currently if you went off-the-shelf to buy this equipment you’d have to have programming skills and know what platform.

“But our self-service systems allow our facilities managers to request these units and then monitor whatever they want. We send these boxes out and the supply chain teams monitor temperatures, moisture and all sorts of things and they are able to get a lot of data back and improve their systems.”

So far, Baker Hughes has been able to save hundreds of thousands of dollars using the equipment, with the figure soon to surpass the million-dollar mark. And this has all been achieved with minimal input from the company’s IT team. Over the next 12 months, the technology will be applied to another 20,000 assets across the Baker Hughes network.

Clark says the drive to develop and implement the original pilot came from a belief that for a very minimal investment, companies can monitor “any number of variables”.

“What we have demonstrated is that it is possible to make an open system at low cost which people can use. With the planned development of the app to set up the devices, we want it to be accessible from both a financial and technology perspective,” he comments.

“In the original project, we were able to highlight three or four significant improvements for a very small outlay, and the club’s reduction in gas use is positive from both a financial and environmental perspective.

“The opportunity is there for companies; just building on this example, if you are responsible for the running of any sort of premise, be it a hotel, a shop or any facility, if someone said that for a few hundred dollars, you might be able to reduce your energy bill by a third then that would be a fairly big incentive.”

The effort to produce accessible and affordable technologies comes from a desire to “democratise IoT”, a phrase that both Clark and Hovnanian mention more than once.

“Over the next decade, IoT systems will sprout and people will make billions out of it, as opposed to currently where people are selling IoT equipment to geeks like me,” laughs Hovnanian. “In the future, you might have a greenhouse that you’d like to monitor for light levels, heat and moisture.

“You can’t do that currently unless you have a lot of techy knowledge, but not too long from now you’ll be able to do that without any skills, and that’s at the heart of what we’re doing. This is something that the world is hungry for, cheap IoT for people with no technical skills is coming. I call this the ‘people’s IoT’.”

No digital team is going to get out of bed for $1,000 so this whole self-service digitalisation could really make a difference

Hovnanian takes his car to illustrate his point. “I drive a 1971 Lancia Fulvia; I do about 6,000 miles a year in it and it would be handy for me to digitalise it so that the basic temperature, oil and tyre pressure can be put into an IoT system, which would allow me to optimise my car every now and again,” he says.

“I could also share that data with other Lancia drivers, who would be happy to receive that information. At the moment, it would cost around £3-4k including resource and time to do this. If I could do it for less than £200 and it would send the data straight through my phone onto a central platform, I would do it in a heartbeat.”

He describes this idea as being like “social media for IoT” and points to fitness apps like Strava where runners or cyclists share their data with each other.

“There needs to be a social media for machines out there, and one of the questions is whether one giant like a Facebook will come along and do that or if it will be more fragmented, with niche networks,” Hovnanian comments.

“Some data you are very happy to share – I’m sure Nick doesn’t mind if people look at the figures from his boiler, so therefore he might classify his information as public. The information that is being sent over the internet is not in any way of a sensitive nature, nobody is going to care about the temperature of the water heater.

“People might then contact him to say they also have a boiler they’ve managed to optimise, and people will begin sharing their stories of how they maintained their machines. That is where a social media aspect becomes really interesting.”